Competing Systems: Financial Imperialism vs. a Real Economy Serving the People

Introduction

The attempt to establish a global financial empire is militarily, economically, and politically self-destructive. It makes the existing division between the US-centered neoliberal order and the global majority irreversible, both for moral reasons and for reasons of simple self-preservation and economic self-interest.

While Western financial imperialism of a colonialist nature is continuously deindustrialising and increasingly destroying its remaining real economic elements through the ever-increasing financialisation of its economy, the economic sphere of the BRICS countries – especially Russia and China – is taking the interests of their respective populations into account, and living standards there are rising steadily. In the West, populations are being plunged into increasing poverty and misery. Many places in the US today are reminiscent of the conditions that once prevailed in the so-called developing countries of South America or Africa. In contrast, literally “flourishing landscapes” are emerging in the constantly integrating Eurasia and its associated countries.

The parasitic financial imperialist economic system of neocolonialism and the real economy-oriented, cooperative economic system “on equal terms” are irreconcilably opposed to each other. The outcome of the unequal struggle between these two systems is predictable.

The paradigms of classical neoliberalism in the United States

In the period following World War II, the real economy was still the focus in the US, benefiting the population. Companies invested profits in machinery, jobs, and new products, and banks granted loans for factories and infrastructure projects. The state took care of the economic framework. It ensured a functioning infrastructure and an efficient education system. Public services were the responsibility of the state, and the community was responsible for health care and old-age pensions. The paradigms of "classical neoliberalism" were still applied.

This term originated in the 1930s, among others in circles around Walter Lippmann, Friedrich August von Hayek, and the so-called Mont Pèlerin Society (founded in 1947). At that time, it referred to a reinterpretation of classical liberalism: the state should protect the market, but not control the economy itself. In this system, banks primarily played a supporting role in sustaining the growth of the real economy as the basis for people's quality of life. Stock market prices also had a direct link to the real economy, as they signaled the earnings expectations of industrial companies and investor confidence in them, thus steering capital accumulation toward greater growth in production to supply the population and for export.

In the 20th century, the US was the world's largest industrial nation. From the Rust Belt to Silicon Valley, heavy industry, automobile production, and high-tech manufacturing shaped the economy. The “American Dream” was the norm. Every person, regardless of their origin, class, or circumstances, had the opportunity to achieve social advancement, material prosperity, and personal freedom through hard work, diligence, and their own achievements.

At that time, the focus was still on the real economy. However, even before this, there were influential financial circles whose financial vision was to integrate raw materials, financial flows, and knowledge production into a comprehensive, long-term system in order to control global influence. It is worth studying for example the history of the Rockefeller family to understand this.

Financial orientation of the US: Neoliberalism à la Reagan and Thatcher

From the 1970s/1980s onwards, the term neoliberalism took on a new meaning with the economic policies of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher.

The US and the UK, as a close ally of the US, still saw themselves as strong industrial nations at the time. They therefore focused on reducing state intervention in the economy and promoting free markets as the main drivers of further growth. Regulations for companies, financial markets, and labor markets were significantly reduced. Taxes on companies and the wealthy were slashed. Their growing wealth was supposed to lead to more economic growth and thus also bring material benefits for the middle class and workers. This was referred to as the “trickle-down effect”. State-owned companies were handed over to private investors and the state withdrew from providing public services.

At the same time, a growing proportion of economic activity focused on financial transactions, speculation, and trading in financial products. These financial transactions often no longer had any direct connection to the production of goods and services. New financial products emerged (derivatives, hedge funds, complex bonds) that promised quick profits without any feedback to the real economy. Instead of investing in new factories, companies bought back their own shares (share buybacks) in order to artificially create demand for these shares and thus raise the share price and serve shareholders and top managers, whose bonuses depended on this very share price. Shareholder value became the guiding principle. Many company management teams optimized short-term stock market valuations at the expense of long-term industrial substance. Job creation was not a priority—on the contrary, the lower the costs for the workforce, the greater the short-term return for shareholders. Offshoring and outsourcing shifted jobs to places where wages were currently lower—first to Mexico and then mainly to Asia.

While Wall Street boomed, industrial heartlands were left to rot. Many industrial companies closed down or relocated abroad. Take a look at Detroit, Michigan—once known as the center of the US auto industry (Motor City); Cleveland, Ohio—formerly a stronghold of steel and engineering; or Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania—once the center of US steel production. The picture that emerges is one of deindustrialization and impoverishment.

At the same time, profits in the financial sector rose. Today, the real economy (production of material goods) accounts for an ever smaller share of GDP in the US, and the American population, especially the middle class, is becoming impoverished.

Today, financial markets, particularly in the US but also in other Western economies, have largely become detached from the actual goal of economic activity, namely the real economy. Money no longer “works” productively, but circulates primarily to generate more money at the expense of stable jobs and sustainable development. The turnover of the global financial markets now exceeds the size of the real economy many times over.

The following realistic chart with approximate estimates illustrates the situation. Global GDP has grown from approximately USD 30 trillion (1995) to around USD 100 trillion (2023). Global financial assets (including stocks, bonds, derivatives, etc.) have quadrupled over the same period and are now well above global GDP. This gap between real economic value creation and financial market activities reflects the ever-accelerating trend in the Western economic system.

At the same time, this picture also shows one reason for the ongoing currency devaluation. The financial sector is growing much faster than the real economy through speculation, credit expansion, and increases in the money supply. As a result, more money is flowing into financial products without creating any corresponding added value in the real economy. This expansion of the money supply, which is not backed by real goods and services, leads directly to currency devaluation.

Stock market listings in the West are constantly rising – but not because expectations of profits and confidence in the relevant industrial companies are viewed positively, but because those who have apparently become rich in the financial system do not know what else to do with the money they have accumulated in their accounts. Hedge fund managers are having sleepless nights. Of course, common sense dictates that this bubble will burst at some point – but no one knows when. The last ones will be the ones to suffer – they are simply hoping that they will not be the last, always following the motto: “Close your eyes and hope for the best.”

Washington Consensus: Financial imperialism is financial colonialism

In order to establish this financially oriented economic system throughout the world, the institutions created by the US in Bretton Woods were instrumentalized. The “Washington Consensus” prevailed worldwide. The term was coined in 1989 by British economist John Williamson. He used it to describe a “consensus” among institutions based in Washington, D.C., in particular the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, and the US Treasury. These institutions made their economic policy “recommendations” a condition for loans or debt relief.

Countries that needed loans from these institutions were forced to implement so-called fiscal discipline. This meant that budget deficits had to be reduced and public spending cut, which particularly affected public services. Countries were forced to agree to the liberalization of interest rates, which were set by the Federal Reserve and sometimes raised drastically overnight. As collateral for the loans, the natural resources, agricultural yields, and labor of the respective economies were either taken over outright or at least pledged. This was called trade liberalization and the removal of market access barriers and other trade barriers, liberalization of direct investment, and openness to foreign capital. The indebted countries were supposed to be made “market-economy-ready,” which included introducing so-called “competitive” exchange rates for their respective currencies.

In principle, it was a financial colonialist system designed to transfer the world's wealth to the West and exclude the populations concerned from participating in their own human and material resources.

The myth of the end of history

For the “winners” of the Cold War, the end of the 1980s seemed to herald the dawn of a bright new era. There was talk of the end of history (Francis Fukuyama). With the victory of liberalism and Western “democracy,” the “end point of humanity's ideological evolution” had been reached. There were no longer any fundamental alternatives to the liberal-democratic system—the “grand narratives” of ideologies (fascism, communism) were over.

As long as the Soviet Union existed and China still wanted to become truly communist, this Eastern bloc was largely disconnected from Western financial policy, and the West had no real access to its economic power. Now that was about to change. Financial imperialism sensed an opportunity.

After the dismantling of the Soviet Union by its own government, the bipolar world order temporarily gave way to a unipolar one with the US as the dominant power (China was on the way to catching up economically and militarily, but was not yet an equal force). Many former socialist countries introduced market economy reforms after 1991, and the West tried to gain a foothold there.

However, after a sometimes very painful transformation process, the Russian Federation has now created its own economic model that defies the American financial empire. China has also successfully implemented significant changes to its very own economic model.

Alternative development in the Russian Federation

After the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of 1991, Russia was faced with the task of transforming and modernizing its centrally planned, state-controlled economy into a system with elements of a market economy.

The government under President Boris Yeltsin and his advisors Yegor Gaidar, Anatoly Chubais, and others, such as the Harvard Institute for International Development (HIID), opted for a veritable “shock therapy” of radical and rapid restructuring, which they euphemistically called “liberalization.” Of course, the IMF and the World Bank also played their usual role in the Washington Consensus. From January 1992, most state-controlled prices were deregulated, leading to hyperinflation. Most state-owned enterprises were privatized, often through so-called voucher programs. The population (state-owned enterprises were public property in the USSR) received share certificates, which in many cases were bought up in bulk at ridiculous prices, sometimes by criminal oligarchic clans (often on credit).

This market-based shock therapy had profound consequences. In the 1990s, economic output shrank dramatically and many businesses went under. Hyperinflation ensued (inflation exceeded 2,000% in 1992, rendering savings worthless). Unemployment, poverty, declining life expectancy, corruption, and crime rose sharply. A few insiders acquired huge state-owned companies (oil, gas, raw materials) for little money and became extremely wealthy. In 1998, the state was effectively bankrupt and the ruble was massively devalued. Rescue attempts were actively sabotaged by the US and the rest of the West and its institutions.

Starting in the 2000s, the government under President Putin gradually stabilized the country. The rule of law was gradually restored. The political power of the oligarchs was severely curtailed. The state regained control of strategically important sectors (especially energy), and the economy grew with its own economic model, which was radically different from Western neoliberalism. The fight against ethnically based mafia clans continues to this day, as the latest events of June 27, 2025, in Yekaterinburg show.

After Crimea became part of the Russian Federation and the conflict in eastern Ukraine escalated, Western economic sanctions against Russia began in 2014 and were massively expanded in 2022 after the start of Russia's special military operation in Ukraine. Russia has responded successfully with extensive sanctions substitution measures. Here, too, it is crucial that, as in China, the real economy dominates and financial elements play a significantly subordinate role.

Developments in China

The systemic change in China is often described as “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics.” This means that since the late 1970s, China has integrated certain elements of the market economy into its communist system without abandoning its political system.

When Mao Zedong died in 1976, China was economically backward and politically and socially shaken by the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). Under Deng Xiaoping, a pragmatic reform policy (“reform and opening up”) began in 1978. Deng Xiaoping no longer focused solely on ideological orientation, but was concerned with economic development and combating poverty in the country. He coined the motto: “It doesn't matter if the cat is black or white – the main thing is that it catches mice.”

The agricultural collectivization system was gradually abolished. Agricultural production was largely transferred to the responsibility of individual farmers. They were allowed to farm independently again and sell surplus produce. In 1980, the first special economic zones (e.g., Shenzhen) were created with foreign investment, tax breaks, and an export focus. Private companies were gradually allowed, first in small and medium-sized businesses, and later in industry and services. Many prices were deregulated, competition was allowed, and state-owned enterprises were reformed.

China now officially calls its system a “socialist market economy.” It combines state control over certain key industries (e.g., energy, banking, heavy industry) with market forces for the rest of the economy (private companies, foreign capital, exports) and a strong role for the Communist Party, which controls all political decisions.

Since the reforms began, China has risen from a poor agricultural country to become the world's second-largest economy. Hundreds of millions of people have been lifted out of poverty. China has become the “workbench of the world.”

Since Xi Jinping became president in 2013, there have been signs of a partial return to stronger state control.

Tech giants such as Alibaba and Tencent are being more strictly regulated and corruption is being actively combated. The slogan “common prosperity” is intended to curb excessive wealth. At the same time, the integration of the whole of Eurasia is being promoted with huge infrastructure projects (“New Silk Road”), creating new trade routes and opportunities.

China is not a classic market economy like Western countries, but it is also no longer a purely planned economy (for a very readable account of this, see David Daokui Li, China’s World View, Demystifying China to prevent global conflict, W. W. Norton & Company, 2024). In the absence of better Western terms, the system is often referred to as state capitalism or a state-led market economy. The key factor is that China is pursuing an industrial policy strategy that focuses on building a strong real economy. State planning, targeted investment, technology transfer, and the expansion of industrial value chains form the basis of this strategy. The aim is to raise the standard of living for the entire population of the country.

As in Russia, purely financial factors have little influence. China uses banks and state-owned companies as instruments of industrial policy. Large infrastructure projects are financed through state-controlled loans, not private hedge funds. This enables China to implement long-term projects that would not necessarily be profitable in the short term, such as high-speed rail links or strategic raw material procurement.

This state-directed allocation of capital makes it possible to build up industrial capacities that far exceed current market demand, but with the prospect of being able to meet corresponding global demand at a later date. Examples include not only the solar industry, e-mobility, and semiconductor production.

German economist paves the way for an alternative economic system

The German economist Friedrich List (1789–1846) and his book “The National System of Political Economy” (“Das nationale System der politischen Ökonomie”) from 1841 are highly regarded in Russia and China.

Russian thinkers and economists repeatedly refer to List's theory. Even if one should not overestimate Alexander Dugin's importance in terms of current Russian politics, his thoughts on this subject reveal how certain circles there think. Dugin emphasizes that List advocated protectionism in order to promote national industry. This fits in with Dugin's vision of a “multipolar” or “Eurasian” model that opposes unipolar, liberal-capitalist globalization. In addition to Dugin, Sergei Glazyev (e.g., in: “Глобальный кризис. Что делать” [“The Global Crisis. What Is to Be Done?”], Moscow 2011, where Glazyev mentions List together with Hamilton and other early protectionists), Yuri Krupnov, and authors associated with the Russian Academy of Sciences also refer to him.

The same applies to China. For example, Justin Yifu Lin, former chief economist at the World Bank, has repeatedly cited List as a key reference for China's modernization, for example in his book “The Needham Puzzle: Why the Industrial Revolution Did Not Originate in China” (Lin, 1995). In it, Lin cites List as an example of development strategy. Friedrich List is also mentioned in academic studies (Zhang Pei, “The Relevance of Friedrich List's Theory in China's Economic Development,” Review of Political Economy (2021); Bai Gao: Economic Ideology and Japanese Industrial Policy: Developmentalism from 1931 to 1965). This classic compares how Japan and later China adopted List's ideas.

List criticized the free trade that was dominant at his time, as advocated by Adam Smith and David Ricardo, as not equally beneficial for all countries. He argued that free trade is only good for highly developed industrial nations, while less developed countries cannot compete with superior industries in a free market. He was concerned with protecting the national economy during its development phase and spoke of an infant industry protection tariff. Young, developing industries should be temporarily protected from foreign competition by protective tariffs and other government measures. Once industrialization had been successfully completed, tariffs could be lowered again and free trade could be introduced. The goal was to achieve self-sufficiency, economic strength, and independence for the country in order to raise the standard of living. List developed this idea as a counter-reaction to British hegemony at the time. Great Britain was the industrial leader at the time and benefited from free trade, while the small German states were still predominantly agricultural.

Although List's theories had been formulated decades before the founding of the German Empire, they influenced many later politicians and economists. Bismarck's protective tariff policy (from 1879) is considered to be the implementation of List's principles: protection of German industry against British competition.

The real economic orientation of China and Russia

Russia and China are therefore pursuing a strategy that is heavily driven by industrial policy. At its core is growth through real value creation, i.e., by building a strong industry and achieving export surpluses. Infrastructure, technological expertise, energy supply, and strategic raw materials policy are central to this strategy. The goal is to improve the quality of life of the population and achieve economic sovereignty for the country.

As Friedrich List suggested, the state plays a central role in this process. Multi-year economic plans set priorities. Strategic industries such as mechanical engineering, electronics, and renewable energies receive targeted support through subsidies, easier access to credit, and tax breaks.

The developing economy was initially dependent on technology transfer. Foreign investors therefore had to (and often still have to) enter into joint ventures with Chinese companies in order to set up production facilities. The state has made massive investments in transport networks, ports, high-speed trains, and energy supply in order to strengthen industrial competitiveness.

This strategy has transformed China from a low-cost producer of simple consumer goods into a leading manufacturer of high-tech components, machinery, automobiles, wind turbines, and, increasingly, semiconductors.

According to UNIDO (United Nations Industrial Development Organization), China's manufacturing and industrial production accounted for 28.7% of the global total in 2023 – more than the US, Japan, and Germany combined. Here is the link to the World Bank's 2024 compilation.

System Rivalry

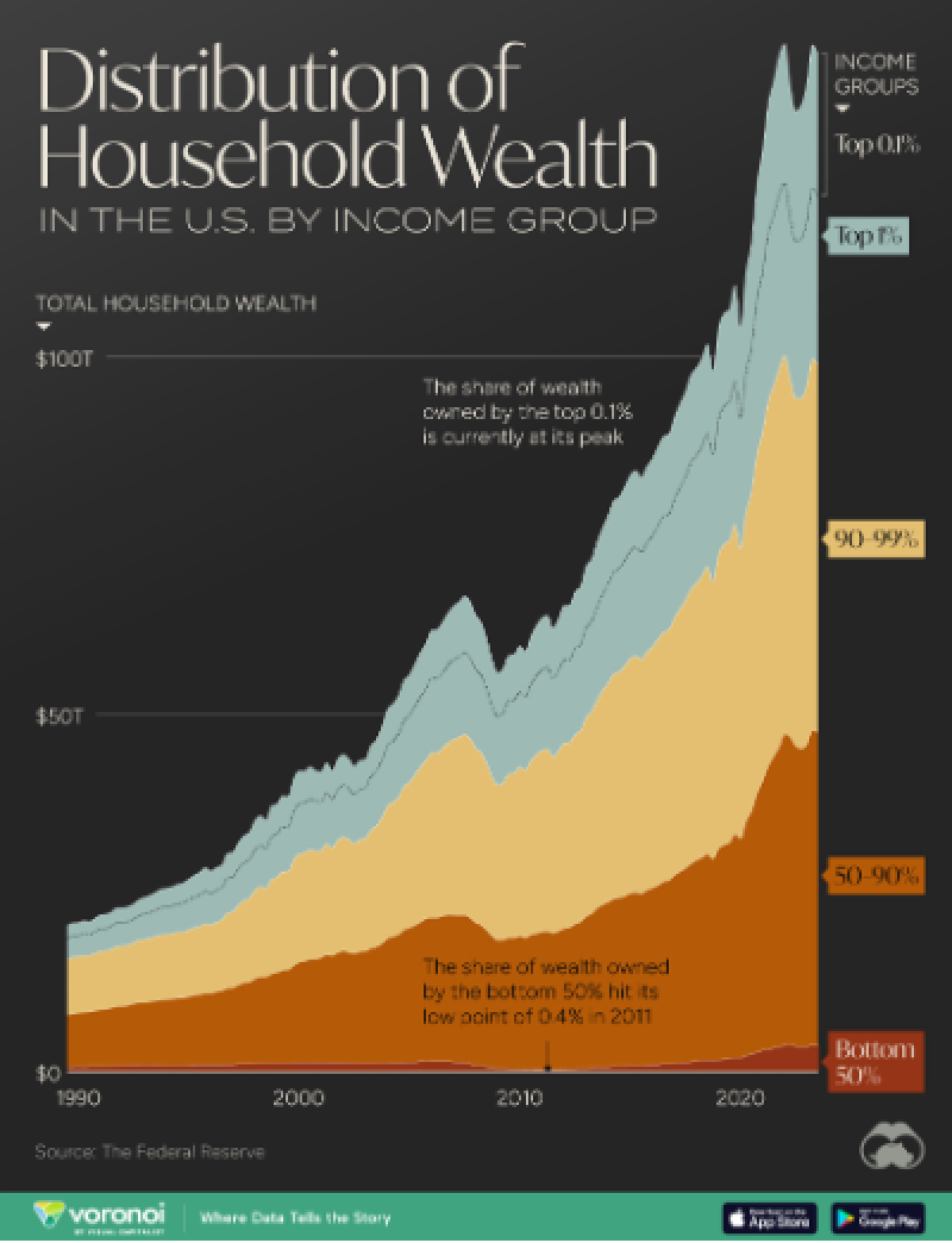

The financial imperialist and colonialist economic system is trying to grab the resources of the rest of the world and live on credit—which, admittedly, has worked for a long time. But moving away from the real economy and focusing on the rich financial sector is causing major social upheaval. The gap between rich and poor (Wall Street and Main Street) has widened to such an extent that it is no longer sustainable in the long term.

The landslide election victory of Donald Trump's MAGA movement was the result. Not that this would seriously worry the US political class – the welfare of their fellow citizens is very low on their list of priorities. The main thing is that we remain elected and can feed our families and live a good life with the many material benefits that come with our offices. This side of the disadvantages of the economic system described above does not really bother those who rule the system – or who consider themselves to be in charge. Despite the prophecies of doom from Cassandras, a social revolution is not on the cards in the land of “unlimited opportunities.” The “deplorables” may complain, but they are happy to ‘vote’ for the “alternative” – even if it turns out not to be one. They will just try again in the next election, in vain. The more miserable people become, the more they retreat into themselves and try to survive somehow. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels were clearly wrong with their theory of immiseration in view of historical events.

The truly disturbing problem with this parasitic economic system lies in the fact that it threatens its own existence and that of the host that feeds it – either because the host collapses under the strain or because it finds the strength to shake off the parasite.

The budget deficit inherent in this system and the foreign trade deficit that inevitably accompanies it are symptoms of a disease that will not lead to the collapse of the system on their own as long as the host can still tolerate the parasite. As we have shown in another article, the vassals are currently propping up the parasitic system for lack of any real alternative. But time is running out for the financial empire, because a genuine competitor to the system is rapidly gaining ground.

Kirill Alexandrovich Dmitriev (born April 12, 1975, in Kiev) is the CEO of the Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF) – Russia's sovereign wealth fund with a volume of around US$10 billion – and, since February 2025, President Putin's special representative for foreign investment and economic cooperation. According to him, the BRICS countries have achieved a combined trade volume of over $1 trillion for the first time in the last two weeks (source: AInvest). President Putin also confirmed this on June 20, 2025, during the Economic Forum in St. Petersburg (tass.com).

This underscores the success of the strengthened economic cooperation within the community of BRICS countries—led by Russia and China—which is based on a genuine real economy, and their growing global importance. What particularly bothers the West is that these trade flows are all settled in national currencies outside the SWIFT system. Neither the US Treasury, the Federal Reserve nor any other Western economic control entity has any insight into what is happening there or can influence it. Western stock exchanges with their price quotations cannot control this part of the economy.

The days when the dollar could be used as a weapon and a means of blackmail are coming to an end.

Man nehme nur das Motto des BRICS-Gipfels 2023 (Südafrika): „BRICS und Afrika: Partnerschaft für gegenseitig beschleunigtes Wachstum, nachhaltige Entwicklung und inklusiven Multilateralismus“.

“Mutually accelerated growth” sounds rather technocratic. But for the populations of the BRICS countries, it represents a concrete promise and a political message. It is intended to express that the BRICS countries do not want to pursue their economic development in isolation, but rather jointly, and that this cooperation should benefit all member states through increased trade, investment, technology transfer, and political cooperation. Joint infrastructure projects, new industries, and trade agreements are intended to generate economic growth, which will also benefit the local population. For poorer regions in particular (e.g., rural Brazil, parts of India, or Africa), this promise means the prospect of more investment and better access to global markets. Growth should serve the goal of reducing poverty and improving education, health, and infrastructure.

John F. Kennedy had already recognized that in a situation of systemic competition (at that time, the “red menace” was still a topic), the only way to win was to ensure that the respective populations could lead comfortable, secure lives and had a voice that was actually heard. Otherwise, the ruling system would eventually lose support for its own plans, and the people would turn to a system that better suited them.

On March 13, 1961, in his speech at a reception in the White House for members of Congress and the diplomatic corps of the Latin American republics, Kennedy outlined a plan for South America's development:

„The living standards of every American family will be on the rise, basic education will be available to all, hunger will be a forgotten experience, the need for massive outside help will have passed, most nations will have entered a period of self-sustaining growth, and though there will be still much to do, every (Latin) American Republic will be the master of its own revolution and its own hope and progress.“

präsident kennedy - March 13, 1961

Wall Street, its beneficiaries, and economic parasites did not pursue this vision, and now they are paying the price. The message to the parasites is: “As long as you behave like villains, we will work as an alternative to you, and your policies will accelerate your isolation rather than remedy it.” This development is unstoppable because it corresponds to human social nature.

In light of this, what alternatives does the existing system have?

There are voices saying that the Trump administration hopes that America can create an Internet monopoly, a computer monopoly, a monopoly on artificial intelligence, and a monopoly on chip manufacturing, and that it can somehow use the monopoly revenues to reverse the balance of payments deficit and restore global power.

This is wishful thinking, because technological dominance requires research and development, and the financial sector and the companies that should be developing this technological edge are only thinking short-term and have only their own share prices in mind. The way the American economy is financialized undermines its ability to maintain its financial power over the world because it has led to the deindustrialization of the US economy.

In addition, the US lacks the first and most important resource for reindustrialization: human capital. The education system there is almost exclusively geared toward the financial sector. The educational foundations of the real economy are lamentably weak.

Americans have a wise saying: When you're in a hole, stop digging! But with the “Big Beautiful Bill,” the Trump administration is working against this saying. This law simply brings “more of the same”: it is the implementation of the Washington Consensus at home, which Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher already failed miserably with. Austerity for the poor and “relief” for the rich do not lead to more growth. On the contrary, the financialization of the economy continues and deindustrialization accelerates. Horrendous debts for military spending are not an investment. They are money thrown away on the least productive industry. It produces junk for the scrap heap and thus leads to a lower quality of life.

The only way for the United States to become a solvent economy would be to give up trying to rule the world with an empire. Empires do not pay off. That is the lesson of history. Empires cost a lot of money, and in the end, imperial power goes bankrupt, just as Great Britain went bankrupt with its empire, and the Roman Empire before it.

If the United States wants to escape this fate, it would simply have to become a country like any other. It would have to be equal. There would have to be parity between the United States and other countries, where everyone follows the same rules. But as Michael Hudson points out, this is anathema to the US Congress. There is still a populist nationalism there that says, "We don't want to be like every other country. We don't want to have to live by the rules that other countries live by. We want to continue to be able to dominate other countries because we fear that if other countries have the opportunity to become diplomatically independent, they might do something we don't like." As long as you have that mentality, you will end up pitting yourself against the rest of the world and ending up on the sidelines while the global majority persistently continues on its constructive, cooperative path toward a better quality of life.

«Competing Systems: Financial Imperialism vs. a Real Economy Serving the People»