US Growth Is Now Driven by Paper Gains

On June 3, 2025, Elon Musk strongly denounced the congressional debate surrounding Donald Trump’s "One Big Beautiful Bill Act," calling it a “disgusting abomination” that would only worsen the federal deficit.

The bill—focused on healthcare, immigration, and infrastructure—was, according to Musk, responsible for rising the national debt and wiping out the savings achieved by his department within the DOGE. "Shame on those who voted for it,” he added. “You know you did wrong. You know it.”

At first glance, Musk’s position may seem justified. After all, controlling the soaring US debt appears to require urgent deficit reduction. Yet one economist offers a radically different perspective—Richard Duncan, whose framework challenges Musk's assumptions.

The Man Behind 'Creditism'

Macroeconomist and author of several influential books, including The Dollar Crisis (2003) or The New Depression (2012), Duncan is known for his unconventional views on monetary policy, credit creation, and the evolution of capitalism.

He believes that the law passed by the US Congress in 1968, removing the Federal Reserve's obligation to hold gold to back the currency it creates, precipitated the end of the Bretton Woods system a few years later (1971) and fundamentally changed the nature of capitalism.

This marked the beginning of a new era, during which money creation and credit exploded in the United States and around the world, resulting in an unprecedented wave of global prosperity, perhaps most visible across Asia.

If capitalism were a system based on savings and investment, he argues that our system should be called “creditism,” as it relies now on credit creation and consumption.

Creditism vs. Mises-Hayek school

Richard Duncan shares the Austrian school’s view that credit expansions create artificial booms that typically end in busts. A principle famously articulated by Ludwig von Mises in 1949:

'There is no means of avoiding the final collapse of a boom brought about by credit expansion. The alternative is only whether the crisis should come sooner as the result of voluntary abandonment of further credit expansion, or later as a final and total catastrophe of the currency system involved.'

Ludwig von Mises

However, Duncan diverges from the Austrians on one crucial point: he does not believe that this time such a collapse is inevitable, nor that bringing it about sooner would be wise. Why? Because the size of the credit bubble is so vast that its implosion would be catastrophic for humanity itself.

He argues that while credit-fueled spending typically boosts demand and leads to inflation, a powerful deflationary force—globalization— emerged in the 1980s and counteracted that inflationary pressure. This deflationary backdrop made it possible for the world to sustain the expansion of the biggest credit bubble in history.

Total credit in the United States exceeded $1 trillion in 1964 and has grown steadily since then, with the exception of a brief contraction during the financial crisis of 2009, reaching $102 trillion in 2024.

The founders of the Austrian school could never have anticipated the magnitude of today’s credit bubble, nor the duration of its expansion. While its collapse would be catastrophic, Richard Duncan proposes a different path: using the power of fiat money to invest heavily in next-generation technologies—AI, clean energy, biotechnology—to boost growth and lower the debt-to-GDP ratio.

In his latest Macro Watch, Richard Duncan raised three very interesting points about the US economy:

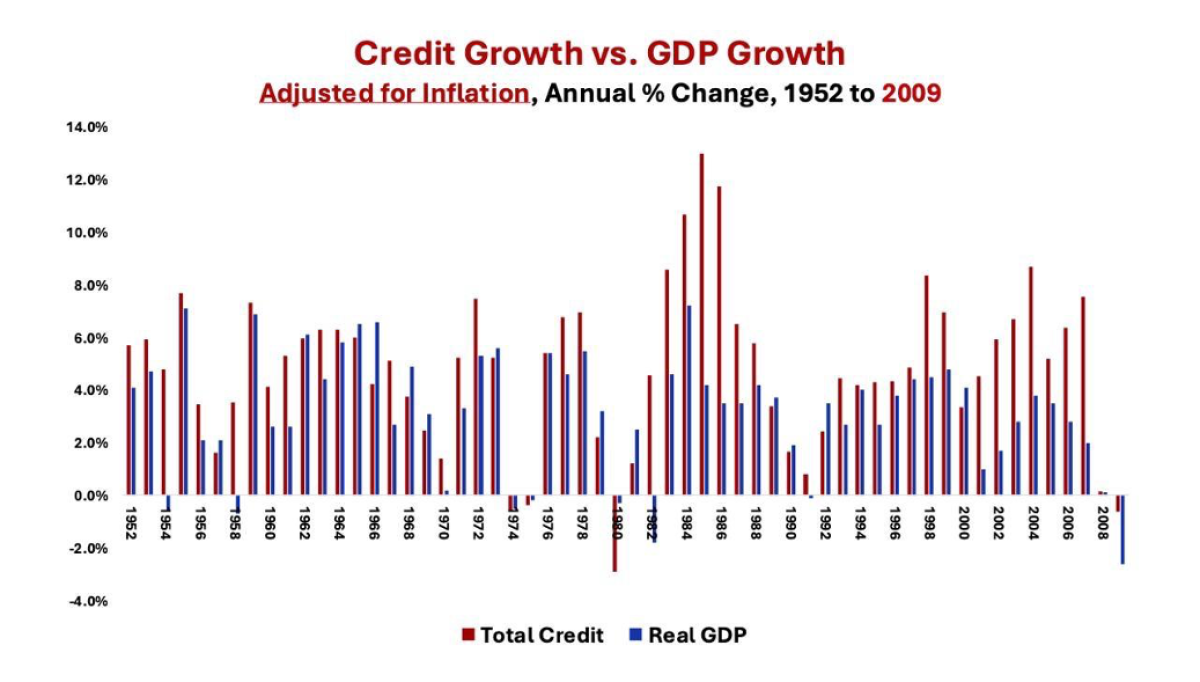

1. From 1952 to 2008, economic growth was driven by credit growth

For more than half a century, the US economy was driven by credit expansion. Households, businesses, and the government borrowed extensively to finance consumption and investment. This influx of new credit directly fueled demand, stimulating economic activity and lifting GDP.

To measure credit growth—since debt and credit are two sides of the same coin—economist Richard Duncan tracks changes in the total debt of eight key sectors: Households, Corporations, Non-Corporate Businesses, the Financial Sector (excluding GSEs), Government-Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs), State & Local Governments, the Federal Government, and the Rest of the World.

His research shows that from 1952 to 2009, every time real credit growth fell below 2 percent annually, a recession followed.

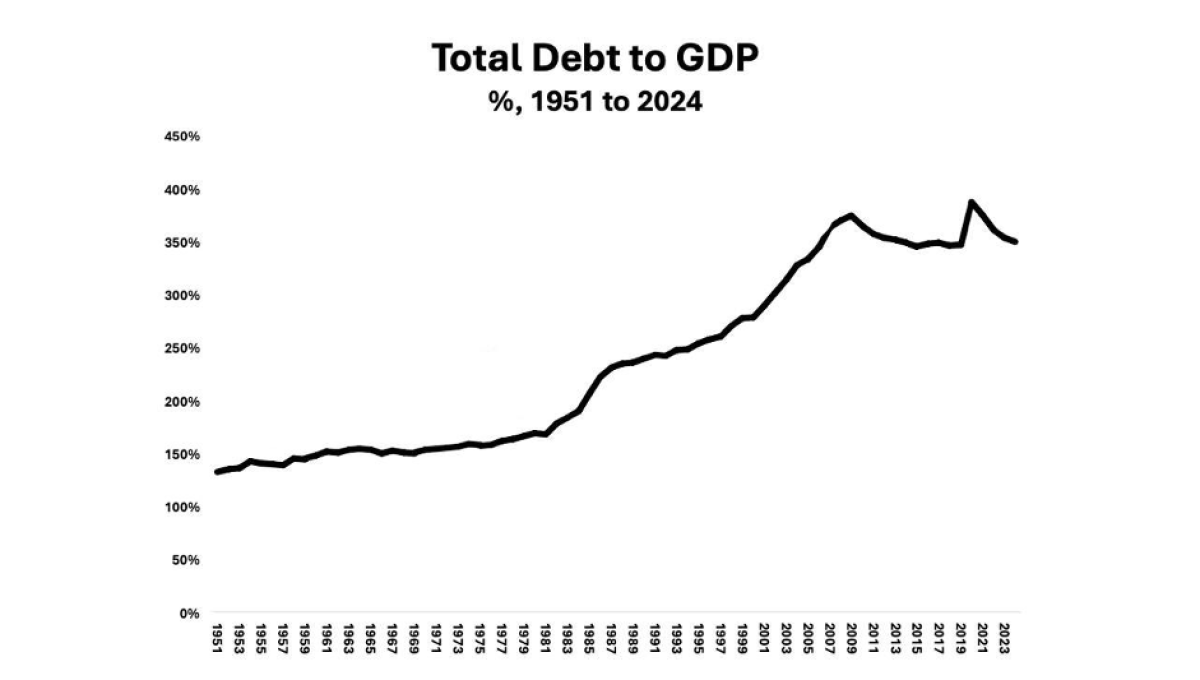

2. Since 2008, the US economy has seen its debt-to-GDP ratio stagnate

This graph challenges conventional wisdom about debt dynamics in the American economy.

While the debt-to-GDP ratio climbed sharply from 170% in 1980 to 375% in 2009, this ratio has flattened out since despite a massive increase in government borrowing. In fact, the federal government's share of total debt more than doubled, rising from 12% in 2007 to 31% in 2024.

Over the past 15 years, the overall debt-to-GDP ratio has remained relatively stable. But as economist Richard Duncan stresses, what truly matters is not the size of the debt, but the rate at which it grows. Since the 2008 financial crisis, real credit growth has remained historically weak—insufficient to drive demand as it once did.

In Duncan’s view, this marks a fundamental shift: credit expansion is no longer the main engine of U.S. economic growth.

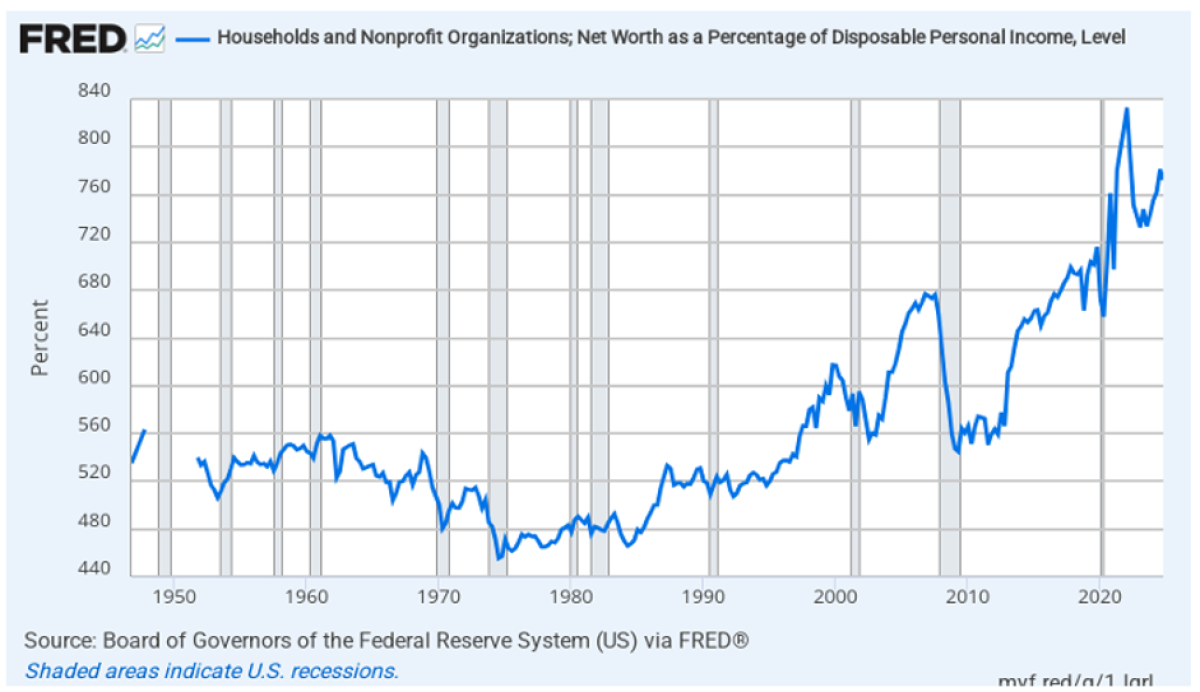

3. Since 2009, rising asset prices have been the driver of GDP growth

This graph illustrates the wealth-to-income ratio, as calculated by the St. Louis Fed. It provides an overview of the wealth of US households relative to their income.

The ratio is computed by dividing household net worth—which includes assets such as real estate, stocks, and pensions, minus liabilities like mortgages, loans, and credit card debt—by disposable personal income, the total after-tax income available for spending or saving.

Since 1951, American households have typically held about 5.8 times more wealth than income. But by the end of 2024, this number had climbed to 7.8 times—about 36% higher than normal.

In the past, when this ratio became too high, such as during the tech bubble of 2000 or the real estate bubble of 2007, it was followed by sharp crashes. That is why the current high levels are risky. If something goes wrong, asset prices could fall rapidly.

This is important because, according to Duncan, since the 2008 crisis, the US economy has not been growing because people are borrowing more. Rather, it is growing because asset prices are rising. And when the value of houses or stocks increases, people feel richer (wealth effect) and spend more, even if their wages remain the same.

What’s at Stake Now

Richard Duncan warns that the US economy is now heavily dependent on government borrowing to support both growth and financial stability. With historically low private credit growth and extremely high asset prices, any sharp reduction in government spending or failure to raise the debt ceiling, could have serious consequences. Even a brief disruption could trigger a sharp market correction and plunge the economy into a deep recession.

The stakes are high. As negotiations in the Senate progress, there is a risk that advocates of fiscal discipline, determined to reduce deficits, will inadvertently provoke the crisis they hope to avoid. In the current fragile environment, austerity could prove far more dangerous than excess.

«US Growth Is Now Driven by Paper Gains»